THE NATURAL, THE (UN)CLEANSED AND THE FOREIGN, LEBANON 2019

THE NATURAL, THE (UN)CLEANSED & THE FOREIGN

Curated by Kaja Kraner and Lucija Smodiš

Featuring: Charbel Samuel Aoun / Nataša Berk / Perla Chaaya, Magaly Jabbour, Elie Azzi, Frederick Zreik, Joanne Nehme, Joy Sfeir and Charbel Samuel Aoun / Enej Gala / Melissa Ghazale / Firas El Hallak / Zuheir Helou / Elie Mouhanna / Maya Abi Semaan / Tomo Stanič

May 10–26, 2019, STATION Gallery, Beirut, Lebanon

“Those singing birds sound like little machines.” / “This waterfall looks like a New Year’s light decoration.”

Could these two statements be paradigmatic examples of current attitudes towards nature and technology? It is not that the nature is technologically mediated; the mediation—as can be deduced from the quotations—is obviously already internalized before it actually happens in reality. A group exhibition of Slovenian and Lebanese artists curated by Kaja Kraner and Lucija Smodiš explores the intersecting dynamics of nature, technology and (self)reflection through various a variety of media—photography, installations, artist book, green sculptures and fractal art.

It is not that nature is alienated through technology in the broadest sense of the word, including cultivation techniques and technological mediation and transformation. Nature has been established as foreign to humankind for some time now, at least within the Western tradition. Humans have always (self)established their identity as natural beings or even animals, albeit with a certain surplus; one of civilization and cultivation, which suggests a potential for overcoming, directing and manipulating our own development, as opposed to raw, instinctive behavior or coincidental evolution. But the current period indicates a different relationship between humans, nature and technology. It is certainly marked by the increasing awareness of the foreignness, even alienness of technology and a certain (potential) autonomous logic and independence of technological means from humans and humanity. Technology is not only becoming more autonomous of its creators, but is also reversing the control humans presumably have over nature. The same nature that has so often been associated with the feminine and that the male-dominated scientific revolution has always sought to tame from its perceived wild character. Namely, technology is artificial, a product of man’s activity through which he established his autonomy and eliminated his subjection to nature and the natural. But at some point it starts to brandish its own potential and threat with its own self-reproductive potential and by that, it threatens to make man redundant. On the other hand, when it comes to the contemporary state of nature and the natural, the discourse on environmental crisis often appropriates science fiction terminology, where we are cast as already living in a pre-post-apocalyptic era, a world without a future

An artwork titled “The grass is greener. (Soft Barrier)” by Elie Mouhanna refers to artificial lawn cultivation and subsequent domestication of nature, which he understands as a symptom of man’s quest for power. Mouhanna’s personal context also comes through in his work since his family has an interesting history regarding lawn cultivation which, at least in the Lebanese context, also functions as a status symbol due to the fact that lawn is time-consuming and expensive to maintain. The specificity of Mouhanna’s work in general is that he tries to expose this quest for power on different social micro levels, usually with its opposition: the soft approaches. Such is also the case with the exhibited artwork that combines the shape of a concrete road barrier, as he himself puts it, used to implement mass security measures within cities, a video document of a waxing moon traditionally connected to vegetational growth and a plant that resembles lawn grass. Mouhanna’s work therefore combines the (symbol of a) trigger of the so-called unconscious impulses of the natural (but is in this case technologically mediated), a symbol of the quest for power within urban environment and a personal view or even an aspiration for cultivating something alive (maintaining the artwork will require a lot of attention indeed).

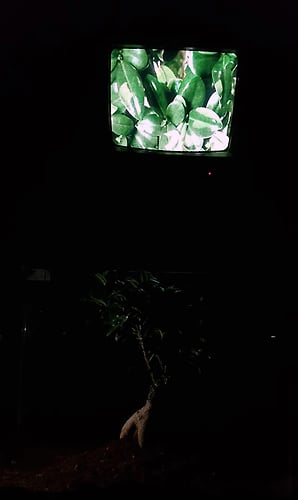

The fluctuation between the natural and artificial is also present in the work of Firas El Hallak. In the work “Videosynthesis” (2018) he made a statement on the younger generation’s attitude towards new technologies, social media and its impact on person-to-person relationships, identity etc. However, in the context of the current exhibition, El Hallak’s work acquires additional semantic layers: the fact that the plant in his installation was usually perceived as a metaphor for a human, for instance, exposes the human need to anthropomorphize nature as a prerequisite for it to become the object of human thought (that is also a frequent subject of criticism). The installation consists of a terrarium in which a plant is planted and filmed by a camera that transmits the video of this very same plant to a television, which in turn is facing the plant and represents the only source of light in a dark room, meaning that the plant cannot survive without it. The living plant as an alleged metaphor for a human (with all of the exposed dependency) also overshadows the fact that the camera is the one that is in a codependent relationship; it cannot detect an image without the light provided by the television.

Videosynthesis (2018) by Firas El Hallak

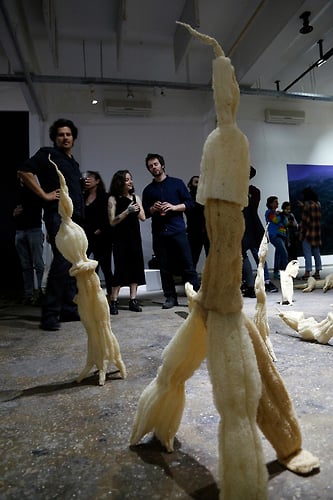

The interlacement between the natural and artificial is enhanced in the Zuheir Helou’s “foreign landscapes with earthly familiarities”. Helou’s fractal landscape animation titled “Geodesy”, in particular, at first resembles Karst landscape, but upon closer inspection we see that it is technologically generated, which makes it weirdly alien and therefore triggers the uncanny feeling of inseparability of natural and artificial. Fractal formula that in the past has usually been used in mathematics in order to generate shapes that are not present in nature in this case becomes a tool to create a simulation of nature. Helou’s aspiration is nevertheless focused on creating an image of, as he puts it, a dystopian alien far-away future; an alien landscape that humans can create either in a stunned state or by using a computer program based on mathematics, both of which require a suspension or overcoming of their existing imaginative potentials. Precisely the latter can be associated with the expansion of fiction in the current age of digital reproduction (for instance in the form of disassociation of a statement from the place of declaration), the so-called post-reality condition that also established science fiction as a relevant starting point to reinvent futurology allegedly eliminated within the frame of contemporaneity. The work of Enej Gala can be interpreted in relation to this, even though he has taken a different approach. In his installation “Another failed alien invasion” he uses a natural material found during his residential stay in Lebanon—luffa sponges—and tries to create an alien micro environment with a humorous reference to popular science fiction scenarios. However, Gala’s fictional installation accompanied by a short statement also refers to the allegedly universal human quest for control, power and territoriality.

Foreign landscapes with earthly familiarities (2019) by Zuheir Helou.

Another failed alien invasion (2019) by Enej Gala

When we talk about the relation between the human and nature, we cannot overlook the already mentioned process of anthropologization of nature, which is one of the key issues of contemporary eco-critique. According to some authors, modern anthropologization of nature was established during the period of Romanticism and has been present both within philosophical thought as well as in the cultural and artistic fields. Romanticism as a formative context or the basis of modern Western knowledge established the paradoxical position of nature in relation to the human/humanity: in order for nature to become accessible to humans, he must anthropomorphize, “domesticate” it (since it is his alleged Other), but this very position of being the Other (of humans, culture and civilization) is also a starting point for romanticization, mystification of nature and so on. For instance in a way that nature becomes one of the privileged projection surfaces of the authentic, unobstructed state of humans, that is, the potential state before their own history and culture.

The artworks mentioned above undoubtedly represent the process of antropologization in specific ways, but the two other artworks presented at the exhibition form an interesting counterpoint in this connection. On the one hand, the work titled “And Still I Breathe” (2014) by Charbel Samuel Aoun is made of the remains of a burnt forest, i.e., a by-product of a natural disaster that is inevitably related to the irresponsible human influence on nature or natural processes. Aoun’s kinetic installation consists of “mortal remains” of the living nature, which are transformed into a simulation of human lungs through movement that imitates breathing. On the other hand, the audio installation titled “Dreams in Time” (2019) takes a different approach of intertwining the human and the natural. The work of Aoun in collaboration with his students Perla Chaaya, Magaly Jabbour, Elie Azzi, Frederick Zreik, Joanne Nehme and Joy Sfeir consists of a bed on pine branches and a sound that emerges from a trumpet and a shotgun surrounding the pillow. With the head between the gun and the trumpet, the viewer can hear fragments of an interview with the Hammana local, a former Lebanese soldier. The short interview in itself could be interpreted as a therapeutic report on dreams (which are in this case highly connected with the political history of Lebanon), but the most interesting part of this report may very well be the ending. At the end of the record the interviewee poetically expresses a desire for humans to become a part of nature, which could be connected to the above mentioned position of nature as a privileged projection surface of the unobstructed human state, i.e., the state without the troubles of civilization (war, political crisis, religious conflicts etc.). The final statement of the ex-soldier, “I wouldn’t want to be the earth, because if something impure pours into it, it adapts. I would prefer to be a tree, because if impurities get to it, it dies,” implies the repulsion towards identifying with the Earth. Unlike a tree, the Earth is, at least for the interviewee, at its core acceptant and in a symbolic sense distant from the concept of finitude. The repulsion towards identification with the Earth can, in this context, therefore also be interpreted as repulsion towards everything humans are still burying into the soil as well as the consequences of these actions (for instance water contaminated with toxic waste).

The artworks mentioned above undoubtedly represent the process of antropologization in specific ways, but the two other artworks presented at the exhibition form an interesting counterpoint in this connection. On the one hand, the work titled “And Still I Breathe” (2014) by Charbel Samuel Aoun is made of the remains of a burnt forest, i.e., a by-product of a natural disaster that is inevitably related to the irresponsible human influence on nature or natural processes. Aoun’s kinetic installation consists of “mortal remains” of the living nature, which are transformed into a simulation of human lungs through movement that imitates breathing. On the other hand, the audio installation titled “Dreams in Time” (2019) takes a different approach of intertwining the human and the natural. The work of Aoun in collaboration with his students Perla Chaaya, Magaly Jabbour, Elie Azzi, Frederick Zreik, Joanne Nehme and Joy Sfeir consists of a bed on pine branches and a sound that emerges from a trumpet and a shotgun surrounding the pillow. With the head between the gun and the trumpet, the viewer can hear fragments of an interview with the Hammana local, a former Lebanese soldier. The short interview in itself could be interpreted as a therapeutic report on dreams (which are in this case highly connected with the political history of Lebanon), but the most interesting part of this report may very well be the ending. At the end of the record the interviewee poetically expresses a desire for humans to become a part of nature, which could be connected to the above mentioned position of nature as a privileged projection surface of the unobstructed human state, i.e., the state without the troubles of civilization (war, political crisis, religious conflicts etc.). The final statement of the ex-soldier, “I wouldn’t want to be the earth, because if something impure pours into it, it adapts. I would prefer to be a tree, because if impurities get to it, it dies,” implies the repulsion towards identifying with the Earth. Unlike a tree, the Earth is, at least for the interviewee, at its core acceptant and in a symbolic sense distant from the concept of finitude. The repulsion towards identification with the Earth can, in this context, therefore also be interpreted as repulsion towards everything humans are still burying into the soil as well as the consequences of these actions (for instance water contaminated with toxic waste).

And Still I Breathe (2014) by Charbel Samuel Aoun

Dreams in Time (2019) by Charbel Samuel Aoun in collaboration with his students Perla Chaaya, Magaly Jabbour, Elie Azzi, Frederick Zreik, Joanne Nehme and Joy Sfeir

Tomo Stanič tackled the common topic by focusing on encounters between different species and at the same time wanted to react to the specifics of the Lebanese context in which he was living for three weeks. In the artwork “Beirut: a dialogue with cats” Stanič nevertheless wanted to avoid giving some big or patronizing comments on the Lebanese society and culture. Stray cats as a subject of research were not chosen by accident since on the one hand, they can be easily contemplated as a parallel for interpersonal relation and are, on the other hand, definitely integral co-inhabitants of Beirut. Stanič derived from the hypothesis that the attitude people have towards cats can be read based on feline behavior that was studied through the artist’s attempt to get as close to them as possible in the process of photographing. The project and methodology were otherwise triggered by an accidental encounter with a graffiti of an anthropomorphized cat with a mustache and a sword on a bullet-riddled wall in Beirut. Intimate relationship/dialogue with cats, which Stanič established during his work on the project, can therefore also be understood as a parallel to the relationship between the foreign and the new cultural environment or the inhabitants of this environment.

Beirut: a dialogue with cats (2019) by Tomo Stanič

In contrast to that, female artists from Slovenia and Lebanon have established a relatively unified topic of the (un)cleansed, cleaning, purification etc., even if in radically different ways, ranging from cleaning as a specific type of labor to cleansing in a wider anthropological and psychological framework. In her famous book Purity and Danger, anthropologist Mary Douglas exposes the relativity of the term clean or dirty as well as the connection between existing cleaning rituals and the process of setting up physical boundaries: between the inside and the outside of the body, geographical and territorial, social and cultural. However, in the case of artists at the exhibition, the topic appears as a practice, maybe a ritual as well, that allows one to get rid of something which for some reason was accumulated almost as trash or dirt (the latter, as Douglas points out, is essentially a synonym for disorder). In this case, a theme that is common to the natural and by it also pollution and the crisis of waste (management), acquires additional, very personal and intimate semantic aspects. The process/ritual of cleaning is a way to (re)establish order, gain control, it enables a new start and has, at least within the Western tradition of thought, a long history that is strongly connected to the relation between the natural and the cultural/civilized, i.e., humans’ immanent environment, as well as to the distinction between man and animal. During the 17th and 18th century the specificity of humans was defined based on the differentiation with an animal that exposed the ability to reflect, to get to know oneself, i.e., to form a (personal) memory, as well as personal and collective history. In contrast, at the end of the 19th century, especially within the realm of arts, the human ability to appropriate some of the animal specifics were recognized as something positive: in order to start over or gain (artistic) innovation, humans must erase their memory and history, their habits, cultivation and previous craft training, they must reestablish a kind of animalistic or even childish purity and innocence that was eliminated through the process of socialization.

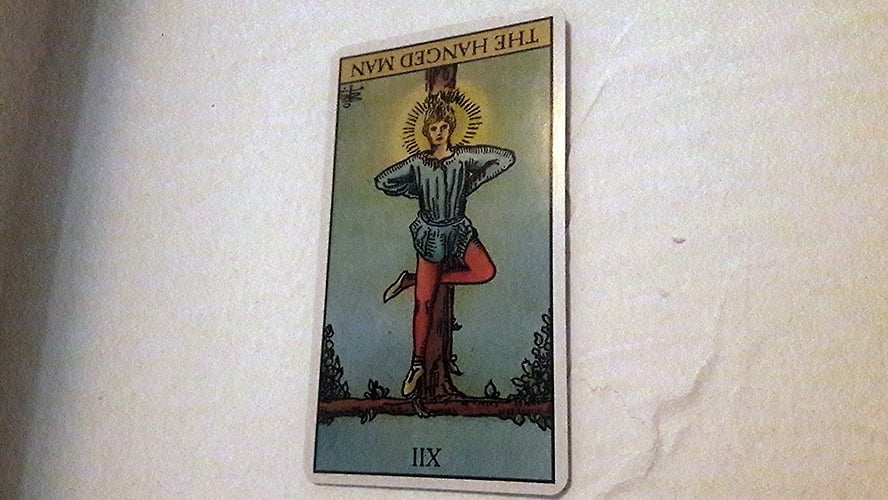

The work of Maya Abi Semaan can definitely be interpreted in this context, considering the artist’s working process. When she was still a child, Abi Semaan has developed a fascination and obsession for collecting objects that were left behind. Since then, she has assembled a large collection of trivial objects, memorabilia and other objects that have, for some reason or another, symbolic value for her. As Abi Semaan explains, this obsession with the “objects left behind” or “trash” changes radically when she takes them from their primal environment and puts them together in order to create an artwork. In this moment she can finally get rid of the things she obsessively collects, she can let them go, which is also the reason why her work process can be, at least to some point, understood as a sort of therapeutic activity. Something similar can also be said for Melissa Ghazale, whose work usually comes from her personal digital archive, the by-product of—as she puts it—the mistake of recording herself constantly. Her work could definitely be contextualized with the contemporary narcissist culture and the deepening of it on the social media (millennials as the so-called selfie generation), but this particular exhibition framework gives it additional semantic layers that connect it to the common theme. Ghazale’s work can therefore be more appropriately framed with the tradition or the self-objectifying working method usually used by female artists in order to reveal the processes of formation of (female) identity (performance and body art since the 1960s). In this case self-objectivation is, as in the case of Abi Semaan, a sort of a therapeutic activity that fluctuates between exteriorization of the collected and becoming a foreigner to oneself as a way to gain control over autonomized and therefore almost unpredictable psychological processes.

The work of Maya Abi Semaan can definitely be interpreted in this context, considering the artist’s working process. When she was still a child, Abi Semaan has developed a fascination and obsession for collecting objects that were left behind. Since then, she has assembled a large collection of trivial objects, memorabilia and other objects that have, for some reason or another, symbolic value for her. As Abi Semaan explains, this obsession with the “objects left behind” or “trash” changes radically when she takes them from their primal environment and puts them together in order to create an artwork. In this moment she can finally get rid of the things she obsessively collects, she can let them go, which is also the reason why her work process can be, at least to some point, understood as a sort of therapeutic activity. Something similar can also be said for Melissa Ghazale, whose work usually comes from her personal digital archive, the by-product of—as she puts it—the mistake of recording herself constantly. Her work could definitely be contextualized with the contemporary narcissist culture and the deepening of it on the social media (millennials as the so-called selfie generation), but this particular exhibition framework gives it additional semantic layers that connect it to the common theme. Ghazale’s work can therefore be more appropriately framed with the tradition or the self-objectifying working method usually used by female artists in order to reveal the processes of formation of (female) identity (performance and body art since the 1960s). In this case self-objectivation is, as in the case of Abi Semaan, a sort of a therapeutic activity that fluctuates between exteriorization of the collected and becoming a foreigner to oneself as a way to gain control over autonomized and therefore almost unpredictable psychological processes.

The Less i know the better (2019), Open up they said, Assemblage (2019), What will remain of you? (2019) Assemblages by Maya Abi Semaan

Untitled (2019) by Melissa Ghazale

Nataša Berk, however, took a radically different position on the topic of cleaning and pollution. In the work she created during her residential stay in Beirut, Berk, who often plays and publicly presents her work under alternative identities, combined her fascination with uniforms and some specifics she noticed in Lebanon, namely the fact that many Lebanese have a domestic worker. Domestic workers in Lebanon, as is often the case, are almost exclusively migrants, either of Ethiopian, Filipino or Sri Lanka origin, i.e., definitely not of Caucasian/white origin. The work of Berk is therefore highly marked with her particular cultural view: the fact that middle-class Lebanese often have maids is something a foreigner who is not accustomed to it notices. If a foreigner’s cultural identity were marked with, for instance, socialist economic and political heritage and therefore also a sensitivity for working conditions and how labor marks or shapes a person’s identity, the position of domestic migrant workers in Lebanon would have probably affected them or even shaken them up. But Berk did not approach the fact that domestic migrant workers who relatively often work almost constantly without having any days off and can be almost a property of their contractor (due to the fact that their passports are often confiscated) in a moralizing way. She has rather taken an approach where she was able, through a minimal intervention, to intensify the already present aspects of the matter. The artwork titled “Maid my day”, for instance, pointed out the fact that maids are neither Lebanese nor Caucasian and that this would be considered inappropriate in a subtle way. Her simulations of fashion as well as tourist selfie photographs with a maid uniform on the other hand underlined the fact that domestic migrant workers rarely enjoy various leisure activities or are the object of view, desire etc., at least not in the same way as Lebanese women or Slovenian tourists in Lebanon.

Maid my day (2019) by Nataša Berk.

During the process of research and exploration of the subjects dealing with the relation between the human and nature as well as the Lebanese context, we came across an image of the so-called Green line. During the Lebanese civil war (1975–1990) a belt of greenery emerged between the front lines. The lack of human presence on the no man’s land enabled nature to reclaim parts of the city, which can be understood as a mutual intertwining of natural creative and human destructive potential.

Kaja Kraner and Lucija Smodiš

Produced by USEK and Pekarna Magdalenske mreže (GuestRoomMaribor residency program), in collaboration with Miha Vipotnik and STATION, Beirut.

Kaja Kraner and Lucija Smodiš

Produced by USEK and Pekarna Magdalenske mreže (GuestRoomMaribor residency program), in collaboration with Miha Vipotnik and STATION, Beirut.